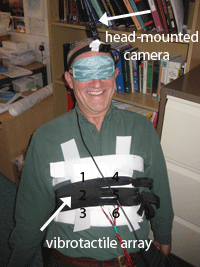

Prototype 5: 2x3 Vibrotactile Corset

Inspired by the pioneering research of Paul Bach-y-Rita, this was our first minimal Tactile Visual Sensory Substitution (TVSS) system. The head-mounted webcam captures a 321 x 240 pixel image which is then split into 6 equally sized cells (107 pixels high by 120 pixels wide) which are thresholded and analysed. The thresholding algorithm compares the grey level of each pixel to a threshold value. If the pixel is below the threshold, it is set to black, otherwise it is set to white. If a cell contains more than a specified percentage of black pixels, the corresponding vibration motor in the vibrotactile array is strongly activated, otherwise it is switched off.

In a first experiment, an 8 year old female blind-folded subject (Laura Bird) wore the TVSS and she had to indicate by raising her hand whether a black tennis ball was rolling down the left or right hand side of a white gently inclined surface. It was found that there had to be sufficient light in the room, otherwise the thresholded image was too noisy and as a consequence a change was made to the software to make the threshold value adjustable. Initially, the balls were rolled too fast and the subject was unable to track the movement because of a lag between the image capture and activation of the vibrotactile array. It was also found that successful tracking of the balls was primarily due to listening to their movement, rather than using the TVSS, and so all subsequent subjects wear headphones.

After some fine tuning of the image processing software, a second experiment was conducted with a blind-folded adult male subject (Andy Clark) who wore headphones. He stood at the end of a table and a black tennis ball was rolled down a very gently sloping ramp. We used the same two alternative forced-choice procedure adopted in experiment one: the subject had to raise the hand corresponding to the side of the ramp that the ball was moving down. The subject positioned his hands so that they did not touch the ramp in case he could pick up vibrations from the rolling ball. He did 25 trials, with the ball randomly rolled down the left or right side of the ramp. In 19 of the trials (76%) he correctly indicated which side of the ramp the ball was rolling down before it reached the end of the ramp. In the unsuccessful trials the subject did not falsely indicate the which side the ball was rolling down, rather he made no indication at all. In one case, this was because the ball rolled down the middle of the ramp, activating both the left and right hand side motors. In the other cases the subject had not positioned his head appropriately and so he was receiving a lot of activation on the vibrotactile array. If subjects could indicate when they were ready, we believe that many subjects could rapidly achieve a perfect performance on this forced-choice task.

There is a movie of some of the successful trials in this experiment on our downloads page.

The main findings were that the initial position of the camera is critical if the ball is to be detected: if it is not over the white rolling surface then there is too much noise in the image. Finding this ‘quiet spot’ was a major challenge for the subject and, unsurprisingly, at no point did the subject feel as though their focus had shifted from the TVSS interface to the environment at large.